We have come so far, yet much remains to be done

March / April 2018 | Volume 17, Number 2

Opinion by Fogarty Director Dr Roger I Glass

As we

mark our Center's 50th anniversary, it's appropriate that we take stock of our accomplishments and also remember our namesake, Rep. John Edward Fogarty. A member of Congress from Rhode Island, he was a staunch supporter of biomedical research and under his leadership of the House appropriations subcommittee with responsibility for health, funding for NIH grew dramatically, from $37 million in 1949 to $1.24 billion in 1967. A bricklayer by trade, he was committed to improving health for everyone, at home and abroad.

"Time and again it has been demonstrated that the goal of better health has the capacity to demolish geographic and political boundaries," he said. "The nations of the world can and must share their knowledge and other resources so that people everywhere may have the blessing of better health, and through health, may move forward to new levels of peaceful productivity."

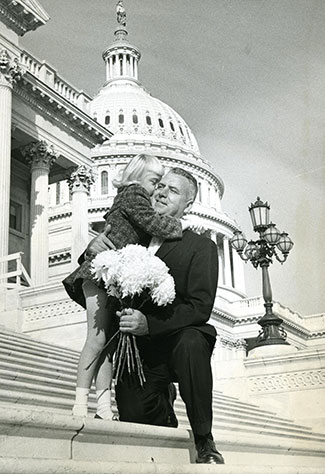

Photo courtesy of the Fogarty family

Rep. John Edward Fogarty, the namesake

of the Fogarty International Center, outside

the U.S. Capitol.

If Congressman Fogarty is looking down on us today, what would he think? How have things changed since he died in 1968? What gains would he notice? What challenges remain? And what are the new health problems that have emerged?

We have come so far, yet much remains to be done.

For instance, in the 1960s, more than 16 million children died each year before reaching the age of five. Through vaccinations, improved hygiene and better medical care, the figure has dropped by more than two-thirds. And yet, 7,000 newborns around the world still die each day, and about five million children do not live to see their fifth birthday.

Another sign of progress is that the scourge of smallpox was eliminated in 1970. Polio, too, has been beaten back in most corners of the earth. And yet, despite our best efforts, isolated pockets of the virus continue to fester. And, even though we are armed with vaccines against cholera, outbreaks of that terrible disease continue in Haiti, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of Congo and elsewhere.

Another formidable challenge emerged in the 1980s, as HIV/AIDS swept across the globe. Back then, a positive diagnosis was a death sentence. Now, because of research advances, the disease can be managed with medication and we've discovered numerous ways to reduce its transmission.

A committed humanitarian, Rep. Fogarty would no doubt approve of the extraordinary effort the U.S. has undertaken with the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), by which Americans have funded new research and provided treatment for 13 million people each year, saving countless lives at home and in low- and middle-income countries. But we still have no vaccine or cure for HIV. And if its spread is not contained among adolescent girls and young women, the epidemic is unlikely to be stopped anytime soon.

On Capitol Hill, Rep. Fogarty would be pleased to see that the strong bipartisan support he helped build for the NIH has only grown stronger. And yet, if we are to maintain our competitive edge in biomedical research globally, to take advantage of genomics, imagine the use of cellphone technologies, big data and other promising developments, we must continue our research efforts to address the most compelling health problems.

We have come so far, yet much remains to be done.

As we mark our 50th year, my staff and I are seeking advice as we ponder the road ahead. What are the most compelling research gaps and unmet needs? Where are the greatest scientific opportunities? How can we best move forward, together, as partners in our critical mission to improve health for all the world's people.

In returning to our namesake, the thoughts he expressed in the 1960s have never been more relevant.

"In the wake of technological advances, the world has shriveled in size. The most distant places are only hours apart. When a child in Calcutta falls victim to cholera or a worker in Mexico contracts smallpox, the mothers of Providence and Kansas City and Los Angeles must be concerned," he said. "The life and well-being of a single individual is a richness beyond all value, a prize without price."

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.