Focus on pain research in LMICs: Research needed to improve access to pain medicines

March / April 2020 | Volume 19, Number 2

Photo by Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

The global burden of suffering from untreated pain is enormous

according to The Lancet Commission on Global Access to

Palliative Care and Pain Relief.

By Susan Scutti

His young Malawian patient had a rare lymphoma causing a painful tumor to grow in his nasal passage, explained Dr. Satish Gopal, a former Fogarty grantee. “We treated him over several years,” said Gopal, who tried to manage his patient’s pain symptoms, but effective drugs remained out of reach. “With his third relapse he was clearly having such severe pain that he chose to end his life in his 20s,” recalled Gopal. “If he lived elsewhere, he may have been cured and lived another 50 years.”

Now director of global health at the NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), Gopal said that patient’s desperation is something that still troubles him.

The global burden of suffering from untreated pain is enormous, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bearing as much as 80% of the burden, according to

The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief. Although morphine is relatively inexpensive, less than 1% of the global supply makes it to LMICs, which is “a medical, public health, and moral failing and a travesty of justice,” according to the Commission’s findings.

“It’s one of the most unequal distributions of any health good that we’ve ever seen in our many decades of work,” said

Dr. Felicia Knaul, a health economist at the University of Miami, who chaired the Commission.

To help quantify the burden, she and her colleagues measured the serious health-related suffering caused by 20 health conditions in all, such as birth trauma, tuberculosis, chronic heart disease, HIV, poisoning and dementia. They identified the physical and psychological symptoms of suffering, and estimated the number of people living with the conditions to produce estimates of the total burden.

They also examined the significant obstacles to providing effective pain relief in LMICs. Evidence must be compiled and presented to policymakers to justify the cost, however nominal, they said. Trained professionals are needed to appropriately manage opioid medications. There are regulatory barriers and concerns of the potential for abuse, as seen in some high-income countries. That’s a mistaken conclusion, said Knaul. “It’s the idea that because there’s serious obesity in the U.S., people in developing countries should go hungry.”

Meanwhile, research to address COVID-19 palliative care and pain relief in LMICs has already taken a back seat to other pandemic concerns. “We need to educate and advocate for the importance of palliative care in the COVID-19 response,” said Dr. Stephen Connor, director of Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance. COVID-19 patients in LMICs will be dying “horribly” from acute respiratory distress syndrome that could be made manageable, said Connor.

Beyond the pandemic, policymakers in LMICs need to increase their morphine requests. South Africa, India, Singapore, Bangladesh and a few other countries currently host scientists conducting palliative care and pain management research that might move the dial, according to Connor.

Knaul believes that convincing governments to prioritize pain management requires a strong set of metrics and “a different kind of research to help rethink the priorities for health.” When using standards like mortality or quality-adjusted life years (QALY) to assess priorities, pain relief will be at the bottom of the list because it typically does not prevent death or make people less sick. The Lancet Commission proposes a new measurement known as "suffering-intensity-adjusted life-year" (SALY) that uses patient reports to quantify averted pain.

This proposed research is “closely linked to advancing value-based care, which seeks to incorporate what patients and their families value,” explained Dr. Afsan Bhadelia, co-lead author on the Commission’s report.

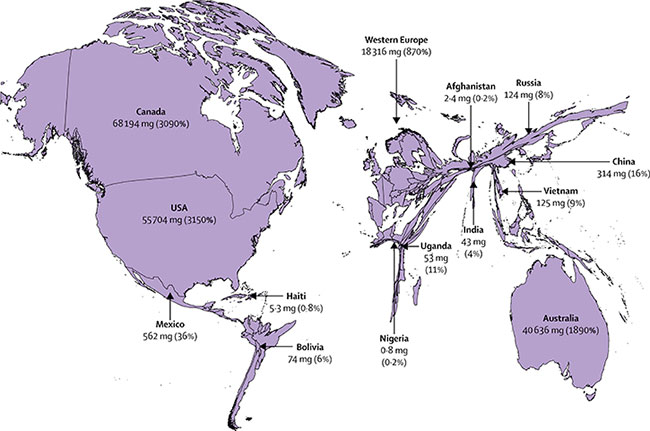

Global Morphine-equivalent Opioid Distribution 2010-2013

Distributed opioid morphine-equivalent (morphine in mg/patient in need of palliative care, average 2010–13), and estimated percentage of need that is met for the health conditions most associated with serious health-related suffering.

Source:

Figure, The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief - findings, recommendations, and future directions

Countries were urged to invest in an essential package of medicines, equipment and human resources to improve pain management for their populations. The Commission also suggested LMICs implement guidelines for opioid use, build awareness of health suffering and better integrate alleviation of pain into national health plans.

Capacity building should also be a priority, Knaul said. “One of the major recommendations was that no physician, no nurse, no social worker, no religious leader should graduate without having at least one course in palliative care and pain relief.” Fogarty training grants might be used to educate global public health students to use some of the measures and techniques developed by the Commission, said Knaul. “We’re also trying to figure out ways to monitor country performance and see changes over time.” In Uganda, for instance, the health ministry has been importing and manufacturing morphine since 1993 and providing national access since 2004 - a model being replicated in a number of other African countries.

Traditional medicine is also relied on for pain relief in many LMICs, especially among rural populations that find it easier to access than medications that require visits to urban clinics. Gopal said that in a study of cancer patients in Malawi, many reported using herbal remedies, dietary modification, spiritual rituals and other practices.

He said he hopes research can be done to rigorously describe the burden of pain in each context - studies that catalog locally implementable interventions and assess their effects. “This is the foundational work that needs to be done with the appropriate level of rigor to move pain control forward.”

More Information

-

The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief - findings, recommendations, and future directions [Open access]

The Lancet Global Health, March, 2018 -

Perspectives: Felicia Marie Knaul: advocate for better pain relief and palliative care

The Lancet, October 12, 2017 -

Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life

WHO, January 2014 -

Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance

-

Bio: Satish Gopal, M.D., M.P.H.

Director, Center for Global Health, NIH's National Cancer Institute (NCI) -

Palliative care development in Africa: Lessons from Uganda and Kenya

Journal of Global Oncology via PubMed, June 30, 2017 -

Pain control in the African context: The Ugandan introduction of affordable morphine to relieve suffering at the end of life

Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine via PubMed, July 8, 2010 -

Hospice and palliative care development in Africa: A multi-method review of services and experiences

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management via PubMed, June 2007 -

Uganda: Delivering analgesia in rural Africa: Opioid availability and nurse prescribing

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management via PubMed, May 2007

Resources and publications related to the article

Pain relief options are limited in low-resource settings:

Resources and publications related to the article

Scientists use mobile health app to mitigate pain in Nepal:

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.