Focus: Fogarty-led project aims to advance emergency care research in low- and middle-income countries

July / August 2019 | Volume 18, Number 4

© 2007 Pradeep Tewari, Courtesy of Photoshare

A man and woman push a stretcher holding an injured man

through the streets of Chandigarh, India.

When someone suffers an injury, heart attack, stroke or other illness that requires emergency care, every minute and decision can affect their chance of survival or the quality of the life they’ll continue to lead. Conducting research in that setting in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) may seem daunting, but it is possible and it’s critical for improving global health, according to the authors of a

new publication organized and supported by Fogarty.

Time-sensitive emergencies or acute illnesses and injuries account for about half of the total burden of disease in LMICs. Yet emergency care research and research training are often overlooked and under-funded, the authors noted.

To help advance the field and raise awareness among scientists, clinicians, academic institutions, policymakers and funders, Fogarty’s

Center for Global Health Studies (CGHS) initiated a project called the

Collaborative for Enhancing Emergency Care Research in LMICs (CLEER). The initiative brought together nearly 40 experts from 16 countries, some of whom are investigators supported through Fogarty’s

trauma and injury research program. The result was a series of six articles published as a supplement to the

BMJ Global Health journal, which provides compelling reasons for investing in emergency care research and capacity building, and addresses the unique challenges developing countries face in this area of medicine.

“It’s an opportune time to identify research priorities and opportunities that can inform and enhance emergency care,” said CGHS Director Nalini Anand. With noncommunicable diseases on the rise, more people will require urgent treatment for coronary diseases or stroke, for example. Traumatic injuries, both intentional and unintentional, are rising especially among young people. Infectious disease epidemics, the increasing frequency of natural disasters and heat waves - fueled by the changing environment - typically take the biggest toll on the poorest communities, as noted by CLEER project lead Dr. Junaid Razzak, a professor of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Based on the changing disease burden and evolving health challenges, I believe, the need for research and the strengthening of emergency care systems is going to be much higher in the future than it is today or ever was in the past.”

Research critical for progress

Improving the quality of care provided in the first minutes and hours of an illness or injury in LMICs is a

“public health imperative,” according to the authors, and will require research and capacity building. By enhancing emergency care systems to include data gathering and research functions, they can help prevent spread of infectious diseases, offer a setting for clinical trials, and serve as a source of epidemiological data to develop disease and injury prevention programs. High-functioning emergency departments (ED) can do more than just provide critical care. They can also help to avert future health issues by engaging with patients who may not otherwise see a health provider.

Photo by David Snyder for Fogarty

Research and research training are needed to advance the

field of emergency care science, according to a series of journal

articles organized by Fogarty.

“A smoker comes in for an ankle sprain and that’s probably the only contact they have with the health system,” said Razzak. “Engaging them around smoking and advising them on exercise is a major plus for health systems.”

Building capacity in emergency care can provide surveillance data to help prevent the spread of infectious diseases, such as Ebola and Zika, and guide governments and health facilities in disaster preparedness and response. This not only contributes to global health security but also helps advance progress in achieving the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The authors point out the need to conduct research and research training in the LMIC context, since high-income solutions often do not work well. Patients in developing countries tend to be sicker on arrival to the ED than those in developed countries where primary care, ambulance service and emergency medical technicians are the norm. Additionally, LMIC patients experience different diseases and respond differently to treatment. “It’s not clear why this is,” Razzak said. “It is possibly related to genetic factors and also nutritional status.”

Training needs detailed

The greatest barrier to progress is lack of human resources, the authors agree. In many LMICs, there is a shortage of hospital personnel with specialized emergency care training, said Dr. Olive Kobusingye, a surgeon at Makerere University College of Health Sciences in Uganda and supplement co-author. Research to demonstrate the value of such training could help make the case to policymakers that it would be a wise investment, she said.

“Quite often emergency room patients have very poor outcomes because the people that care for them are trained to care for general patients, but they don’t have the skills to pick up on what’s going on in this patient in the next so many minutes and what they need to do to save their life,” according to Kobusingye.

Few academic institutions in LMICs have emergency medicine departments, which also means there is little leadership for the field. One article highlighted a Fogarty-funded

trauma and injury research training program in Pakistan, which has produced high-quality research and enhanced the pool of local researchers. Razzak, who spends a significant part of his time in the country, is among the principal investigators on the project. “If such programs as Fogarty’s didn’t exist, I wouldn’t have been able to create a specialty in Pakistan or push along the development of research and education together.”

Photo courtesy of Dr. Junaid Razzak

Many developing countries lack resources to effectively provide

emergency care.

Data required to inform policy

Because emergency care surveillance and detailed registries with longitudinal data are largely absent in LMICs, policymakers and health facilities have little science-based information to guide their decisions on how to allocate resources and what services to provide.

Data on the causes, risk factors, treatment, outcomes and costs of emergencies can support public health in multiple ways, according to the CLEER working group that focused on surveillance and registries. In their article, they note the information has the potential to define the burden of emergency conditions and variations within and between countries; describe the prevalence of modifiable risk factors; outline the process of care and its impact on access and outcomes; and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of interventions, for example.

Different patients put different demands on the health system, said Kobusingye. “One trauma patient could use resources that maybe would go to 10 malaria patients.” She said it’s important to provide relevant information to the authorities who plan services.

The authors provide a framework for conceptualizing opportunities for surveillance and registries that divides care into three phases: pre-hospital, facility-based emergency care and post-emergency care. And they suggest possible sources of data beyond that collected at a health facility, such as ambulance records for road traffic injuries, police records for interpersonal violence, and insurance and labor information on workplace injuries.

Given that paper records are still common in LMICs, and an over-burdened ED staff may be frustrated by data collection, the authors suggest identifying and prioritizing what is most important to the emergency system and using standardized clinical documentation.

Research needed in LMIC context

Clinical research in emergency care in LMICs is rare, but the investment will make care “more effective, responsive and appropriate for the population,” the authors noted.

What works for patients in developed countries may not translate to the LMIC context. For example, the authors note a Fogarty-supported study that found

guidelines for treating sepsis in a high-income country protocol had harmful effects when used in Zambia.

Several constraints to conducting clinical research were identified, including a lack of consistently applied, relevant and reproducible metrics. Leveraging technology represents a “promising” opportunity to improve emergency care, the authors suggested. Tablet-based data collection tools, text messaging for rapid patient follow up and telemedicine for improved patient diagnoses all hold potential. Distance learning and other non-traditional media should be studied to see if they can be efficiently implemented for research training.

Unique ethics questions posed

Research in any emergency situation raises ethical questions. The concerns are heightened in LMICs where ED patient volume is high, staff is overburdened, health infrastructure is weak and populations are especially vulnerable. Despite all that, it is “possible and essential to global health,” to conduct ethical emergency care research in developing countries, according to the CLEER working group that focused on ethics and produced a

paper outlining several distinctive challenges.

© 2012 David Davies-Deis, Courtesy of Photoshare

A traffic accident in Abuja, Nigeria.

Assessing the risks and benefits of an intervention may be complicated by the fact that LMIC patients are often sicker when they arrive at the ED than those in HICs, and may also have underlying concerns such as malnutrition. The global standard of care may not be available or is too expensive. In the urgency of the ED, there may not be time to clearly differentiate the role between the clinician providing care and the researcher seeking consent. Researchers and research ethics committees need to be mindful of the multiple ways in which potential participants may be vulnerable, the authors suggested. For example, can they make their own decisions, or do they require extra privacy because of a stigmatizing issue? Excluding vulnerable populations raises another set of concerns - will that bias recruitment or deny people potential benefits? Obtaining quality, fully informed consent from patients or families, or waiving consent, is another ethical challenge. Engaging the community in the research process may provide some protections.

The ethics working group reviewed human subject research regulations in a dozen LMICs and found they vary between countries, but most would allow for a substantial amount of emergency care research. However, there are no internationally accepted guidelines for the ethical review of this research and much of the bioethics literature focuses on issues relevant to HICs. As a first step, the authors proposed an international conference to set an agenda for harmonizing emergency care research ethics practice in LMICs.

Demonstrating the economic value

Emergency care delivery systems, unlike other health care components, must be available to people 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If they are not well organized or adequately financed, it can lead to catastrophic health spending that can impoverish families.

In an

article exploring the economics of emergency care, authors note that when people can’t access quality emergency care - either because it’s unavailable or unaffordable - they delay or forgo care, which leads to higher morbidity and mortality. That then takes a larger toll on society because of lost wages, lower productivity and higher costs of long-term care.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that emergency care interventions can be a wise investment, the authors said. Their literature review produced 15 examples of research that demonstrate the cost effectiveness of a variety of interventions studied in LMICs.

More research is needed and the authors identify several priority areas that include: the methodology of economic evaluation for emergency care interventions; understanding the interplay of various health financing mechanisms on financial protection for unexpected catastrophic illness; interpreting the societal effects of poor coverage protection; identifying the health and economic impact of emergency care interventions; and defining the place of emergency care financing among other competing social priorities.

Ensuring high-quality delivery systems

Emergency care systems (ECS) in LMICs are fragmented - lacking coordination and accountability, according to supplement authors. Recognizing the complexity of these systems, the publication contains a

proposed framework to approach conducting ECS research. The co-authors also identified a series of priorities and point to a selection of studies from the limited research that’s been done in LMICs.

While there are challenges, the authors agreed “the potential impact of research that uses such a framework on evolving ECS in LMICs could have a tremendous impact optimizing systems to impact morbidity and mortality.”

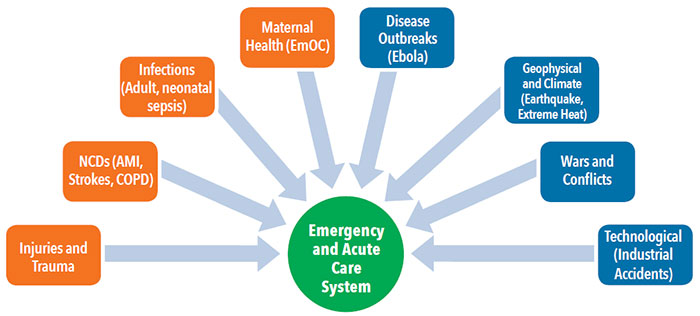

Scope of emergency care

Time-sensitive illnesses are responsible for the majority of the disease burden in low- and middle-income countries. A strong emergency care system can improve the outcomes of conditions affecting individuals, including heart attack, stroke, sepsis and trauma (shown in orange), as well as those resulting from public health emergencies such as wars and natural disasters (depicted in blue). See

full description below.

Issuing a call to action

Looking ahead, the CLEER participants believe emergency care research holds much potential. They call for strengthening emergency care research capacity, providing opportunities for collaboration and networking, increasing support for research and training from funders and philanthropic organizations, standardizing definitions of outcomes and exploring the use of technology for emergency care research.

The co-authors see the CLEER initiative as the first step in a much-needed effort to build and sustain a community of emergency care researchers, committed to working together to advance the field. Razzak also hopes that the supplement will help broaden support for LMIC emergency care research among the 27 Institutes and Centers at NIH, since so many of the research questions are cross-cutting.

“The challenge is how this movement can be sustained over the next few years,” he said. “If you bring the right people together, good things will happen because everyone is so passionate.”

More Information

Description of scope of emergency care flow chart: Eight categories of emergency care flow centrally toward a central Emergency and Acute Care System. Four categories of conditions affecting individuals: Injuries and Trauma; NCDs (AMI, Strokes, COPD), Infections (Adult, neonatal sepsis); Maternal Health (EmOC). Four categories of public health emergencies: Disease Outbreaks (Ebola); Geophysical and Climate (Earthquake, Extreme Heat); Wars and Conflicts; Technological (Industrial Accidents).

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.