Bioethics: protecting lives in service to research

November / December 2011 | Volume 10, Issue 6

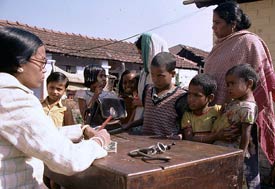

Photo by Ray Witlin/World Bank

Bioethics guidelines are intended to protect all

human research subjects, with special provisions

for studies of illiterate populations and children.

By Steve Goldstein

A young African woman, pregnant with her first child, lives in a small village with only a traditional healer to provide care. She suspects her husband died of HIV/AIDS but he was not tested. Some scientists visit her village and ask its leader for permission to study any women who are about to give birth, so they can test drugs that might protect the babies from HIV. The village elder agrees. When the researchers approach the woman, she is afraid to receive drugs that might harm her baby. But she is also terrified her baby will die if she doesn't accept treatment. She doesn't want to antagonize her leader, so she goes along with the trial. Although she is illiterate and didn't understand the researcher's description of the study, she marks an "X" on the form and agrees to participate.

Scenarios such as this one pose a number of thorny ethics questions for researchers attempting studies in settings with severe poverty, sex inequality and little access to basic health care. How can scientists ensure consent is freely given, and that the subject understands the proposed clinical trial and any risks? Is the possibility of access to treatment an unfair inducement? What obligation, if any, does the researcher have to treat the woman if she is found to be HIV positive? How can the woman's privacy be preserved in her small community? What benefits should the village receive from the results of the study?

Bioethics and the protection of human subjects are the foundation that enables clinical research. The combination of the globalization of the biomedical industry, outsourcing of clinical trials to developing countries to cut costs and avoid regulation, and the surge in research activity to address HIV and malaria has been overwhelming, given the lack of developing country researchers with formal training in bioethics and the scant infrastructure to provide oversight.

"In order to preserve the health of society and its overall humanity, it's important that research be conducted in an ethical fashion," according to Nigerian scientist, Dr. Clement Adebamowo, who directs the Fogarty bioethics program at the University of Ibadan. (Learn more about Dr. Adebamowo's work in the article Bioethics takes root in Nigeria.) "Invariably some participants will go before others in helping us to understand diseases, the treatments and the impact of those treatments. So, we owe those participants a debt of gratitude and we have a duty to protect them."

Concern for research subjects grew from the horror of the Nazi experiments on humans, spurring an effort to lay out ethical guidelines in the Nuremberg Code in 1947, followed by the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki in 1964. The field of bioethics was largely the domain of philosophers and theologians until 1970s, when the tremendous growth of biomedical science expanded it to a multidisciplinary endeavor involving anthropologists, policy makers, physicians, sociologists and the public at large.

"Most countries around the world do not have laws or norms about research ethics locally," said bioethics professor and Fogarty grantee Dr. Nancy Kass, of Johns Hopkins University. "You can find many places where nobody has ever talked to researchers about the importance of asking permission before they do research. And nobody's talked to researchers about making sure a third party looks at their research before they go into the field. But in every country I've worked there are plenty of people who appreciate that it is very important to follow international standards of research ethics."

Photo by David Snyder for Fogarty/NIH

Fogarty’s bioethics training program helps

researchers communicate more clearly with

potential study subjects so they understand

what is involved and can give informed consent.

One reason is that, to receive NIH grants, research studies must be designed and implemented to conform to the same standards as U.S. clinical trials. In locations with little expertise in bioethics, that can be extremely challenging.

Begun in 2000, Fogarty’s International Research Ethics Education and Curriculum Development Award is designed to develop culturally relevant bioethics curricula for developing country scientists and support training to produce leaders who could advise on policy and help train the next generation. In the last decade, Fogarty has enabled more than 560 developing country scientists and administrators to complete master’s level training in bioethics. Kass, who has run Fogarty-supported programs in Africa, said, "What Fogarty has created with minimal funding and the impact that these programs have had is remarkable."

To leverage the effort, Fogarty has partnered with other NIH Institutes and Centers to expand training efforts. Co-funders of the program include The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). In addition, the NIH Clinical Research Center provides significant leadership and expertise, as well as online and in-person bioethics training courses geared to developing country researchers.

Some key bioethics issues for researchers who work in developing countries:

- Have subjects granted truly informed consent? Have they fully understood the information presented, including any possible risks?

- What’s the appropriate standard of care for the study participants? If researchers discover in a malaria study that a participant has HIV, do they have a responsibility to treat that disease? What is their responsibility to provide care after the study is concluded?

- What measures are being taken to ensure the participants’ medical information remains confidential?

- As genomics advances and DNA analysis is increasingly part of clinical trials, how can participants’ samples be protected?

- How are the research priorities determined? How does the community benefit?

- Increasingly, studies take place at multiple sites in multiple countries. How should differing sets of rules be managed?

"The problem is that good ethical research requires a lot from top to bottom - from what questions to ask, how to design studies, how to do them, how to get them designed in a way that recognizes risks," said Dr. Christine Grady, acting chair of the bioethics department at the Clinical Center at NIH.

Many bioethicists agree that regulation is necessary but not sufficient to ensure ethical research. Examination by an ethics committee or an Institutional Review Board (IRB) only goes so far. Training is geared to creating a culture of responsibility, so that it's accepted by investigators, the teams that work with them and institutions that host them. "You can still get an unethical result even if rules are followed," said Grady.

Changes to the IRB process are under discussion in the United States, much of them involving streamlining the process. Because the bureaucracy has been viewed by some as cumbersome and investigators regard it as a burden, they may try to avoid it, ignore or outsource it to a third party.

The review process is critical. "If the review is done incorrectly, you risk people getting harmed," said Dr. Joseph Millum, bioethicist at Fogarty. "If you do it inefficiently, you hold up the process of research." The IRB is further limited by its function, reviewing the protocol and the consent form, but not overseeing the actual research process.

Fogarty's program aims to produce bioethics leaders who can advise developing country institutions how to formulate and strengthen local bioethics guidelines, build well-informed review bodies capable of evaluating research proposals, and train others in the principles of ethical research conduct. Given the increasingly collaborative nature of research, it's also important to bring new voices with different perspectives to the global ethics conversation.

Fogarty's Dr. Barbara Sina, who has managed the program since its inception, said she's encouraged at the progress developing country trainees have made. "Our ultimate goal is to develop research ethics capacity and expertise so that countries can create their own ethical oversight processes and participate equally in the global dialogue on research ethics."

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.