Because of a lapse in government funding, the information on this website may not be up to date, transactions submitted via the website may not be processed, and the agency may not be able to respond to inquiries until appropriations are enacted. The NIH Clinical Center (the research hospital of NIH) is open. For more details about its operating status, please visit

cc.nih.gov. Updates regarding government operating status and resumption of normal operations can be found at

opm.gov.

Africa transforms its medical education with Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) - Page 1

September / October 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 5

By Cathy Kristiansen

(Page 1 of 2)

Page 1 | Page 2

Sweeping changes are taking hold in sub-Saharan Africa to dramatically transform medical education. Universities are broadening the subjects covered, recruiting and retaining well-qualified faculty, employing state-of-the-art teaching tools, developing regional training centers and upgrading technology to enable distance learning and resource sharing among institutions.

Driving this movement is the U.S.-funded Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI), launched two years ago to increase the quality, quantity and retention of health care workers and the faculty needed to train them. The program is investing about $130 million over five years through direct awards to African institutions in a dozen countries. Funded by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the NIH, MEPI is co-administered by Fogarty and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

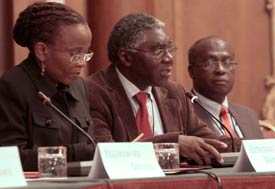

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty/NIH

A dramatic transformation of sub-Saharan medical

education is being fueled by funds from the U.S.

government, including the NIH. The initiative is

raising the quality and quantity of health care

workers and devising ways to keep faculty on staff.

"I've never seen this kind of enthusiasm and excitement," said Dr. Nelson Sewankambo, who manages the MEPI award to his institution, Uganda's Makerere University, and heads the council of his MEPI peers. "The initiative has brought an unprecedented opportunity. It has really gotten people very interested in doing something about medical education with the purpose of improving people's health on the continent."

MEPI stakeholders recently met in Ethiopia to assess progress. Fogarty Director Dr. Roger I. Glass said the awards are proving to be catalytic. "This program really is a game-changer, opening a door for universities and hospitals to be creative in how they move ahead in medical education and science. Governments now see medical education as a priority for their countries."

Unlike many programs for lower- and middle-income countries, MEPI directly funds African grantee institutions. This encourages local ownership and allows each country to adapt the program to suit its unique resources and health needs. Grantees are required to collaborate with their national ministries of health, education and finance to ensure goals are aligned with country priorities and to sustain progress over time.

Courtesy of the MEPI Coordinating Center

Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI)

grantees and collaborators met recently in

Ethiopia to review progress made in the

program's first two years.

"This has been something wonderful," said Dr. James Gita Hakim, who runs the University of Zimbabwe's MEPI. "African institutions have been empowered not just administratively but financially."

All the sites have ramped up recruitment of faculty and have dramatically increased the number of students in their programs. Under MEPI, grantees partner with high-income country institutions, which offer expertise and advice during the transition.

"I am particularly impressed by the ownership and sense of teamwork the principal investigators are developing," said Dr. Joseph C. Kolars of the University of Michigan Medical School, a partner in Ghana's MEPI project. "Leadership of the African medical schools is in the driver's seat, directing, shaping and managing medical education. This is a different funding model."

Strengthening medical curricula

MEPI has led to a fundamental change in the way African institutions and government leaders approach medical education, project leaders said. Traditionally, teachers were physicians or nurses who passed along their knowledge without further specialized training and with little consultation outside their departments. Students received didactic instruction via lectures but often lacked hands-on experience in skills labs and access to up-to-date online information and learning tools.

Through MEPI, grantees are pursuing entirely new educational approaches. "Now, we see medical education as a whole profession by itself. I think by the end of the program, we are going to have a really strong faculty, much stronger than any of us had imagined," said Zimbabwe's Hakim.

Photo courtesty of Photoshare/Lisa Basallaby

Africa suffers a quarter of the world’s disease

burden but has only 3 percent of its physicians.

MEPI-funded institutions are building capacity

for medical education, both in cities and in rural

areas where most of the population lives.

Institutions are changing curricula content and format, plugging education gaps and expanding the breadth and depth of subject matter - mostly in medicine, but also in nursing and dentistry in some countries. Participants are incorporating more multimedia resources, including grand rounds lectures by experts, procedure demonstration videos and current online journal articles. By using technology to network medical schools together, teaching tools can be shared, ensuring all students receive high-quality instruction, including those in training at rural sites.

The University of Nairobi, for example, is expanding hands-on learning with MEPI resources. It has equipped a new multidisciplinary skills lab so students can practice procedures - including episiotomy repair, lumbar puncture, blood pressure measurement and catheterization - on dummies before attempting them on humans. For the first time, the university is integrating distance learning as an option. It estimates 20,000 nurses can earn advanced degrees at their work stations rather than by traveling to Nairobi to attend classes.

In Durban, South Africa, the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal (UKZN) is expanding its approach to the disease. For instance, it's introduced basic science courses in HIV virology, diagnosis, immunology and pathogenesis.

To prepare final year students to confidently treat HIV/AIDS patients, bridging the gap between theory and application, the university designed an HIV enrichment workshop that includes case studies, clinical guidelines and government policies. Aside from medical student training, UKZN packaged a series of workshops to enhance sensitivity about HIV/AIDS among health workers. Called "Me and HIV," the workshops examine the myths, realities, attitudes and perceptions of HIV/AIDS, prevention strategies and how to help people learn to live with their condition.

Photo by Richard Lord

for Fogarty/NIH

By conducting medical research,

faculty can enhance their work

satisfaction and career

achievements, so are less likely to

leave their jobs. Research findings

also contribute to locally relevant

health knowledge.

Broadening to include chronic health problems

Because of its high burden of infectious diseases, sub-Sahara has focused its medical training on that area. However, MEPI seeks to develop much-needed expertise in other health fields - such as emergency medicine, surgery and maternal and child health - and also tackle the rising tide of chronic problems, including cancer, heart disease and mental health disorders.

For instance, Zambia suffers from high rates of maternal and neonatal deaths, which UNICEF estimates at 590 mothers and 3,400 newborns per 100,000 births. The University of Zambia is taking steps to lower these deaths, not only by improving medical training in general but also by developing clinical care guidelines for neonatology, certifying more trainers in emergency obstetrics and newborn care, and setting up monitoring and evaluation systems to identify problems that need the most urgent action.

The university arranged monthly inter-departmental meetings, which have already brought results. Faculty took up the issue of hypothermia in neonates transported from the delivery room to the intensive care unit. This led to better swaddling of the babies and fewer deaths. A study of maternal care prompted closer monitoring of blood bank stocks, reducing deaths from postpartum hemorrhaging.

In Uganda, Makerere and Mbarara universities are tackling cardiovascular disease. They've introduced specialized faculty training, new courses with related research components and more facilities, such as a cardiac catheterization laboratory. So far, nearly 300 students have taken these targeted courses and several have launched research projects, for instance, on the pathogenesis and progression of heart disease and air pollution's effect on lung function.

HIV-associated malignancies, which are severely under-diagnosed, are a MEPI focus topic at the University of Malawi. Aside from training scientists in surveillance, the university is preparing more histopathologists - experts in the study of organ tissue. It's also instructing pharmacy technicians and nurses on how to handle chemotherapy drugs and is training physicians to do biopsies of Kaposi's sarcomas.

Courtesy of Komfo Anokye

Teaching Hospital, Ghana

Students in Ghana learn emergency medicine using

skills laboratory models. MEPI funds are

contributing to new lab equipment, curricula,

multimedia resources, research projects and

other education-enhancing changes.

"MEPI seems to have a snowballing effect," said Malawi project leader Dr. Johnstone Kumwenda. His institution sent two trainees to learn pathology at UKZN. "We can see people are now hungry to get into pathology training. If you provide the opportunities, people will grab them."

A neglected medical field in many African countries is mental health. With only one psychiatrist on faculty, the University of Zimbabwe devoted some of its MEPI funds to develop additional mental health expertise, in collaboration with institutions in the U.S., U.K. and South Africa. The university now has three psychiatrists, including one specializing in children, and student enrollment in mental health courses has risen significantly.

Ghana's MEPI project focuses on emergency medicine, the first such program in West Africa. In a multi-pronged approach, Kwame Nkrumah University is working with five other training centers to develop medical and nursing curricula and training in handling injury and acute medical illness. Participants are learning emergency medicine research methodology, administration and management.

Page 1 | Page 2

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.