What do you mean when you say "capacity building?"

July/August 2025 | Volume 24 Number 4

Photo courtesy of Johns HopkinsDr. Yukari Manabe

Photo courtesy of Johns HopkinsDr. Yukari Manabe

“I didn't know what

capacity building meant until I went to Uganda, and then someone said that phrase to me every hour,” says Dr. Yukari Manabe, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Between 2007 and 2012, she served as head of research at the fledgling

Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), founded in Kampala in 2002.

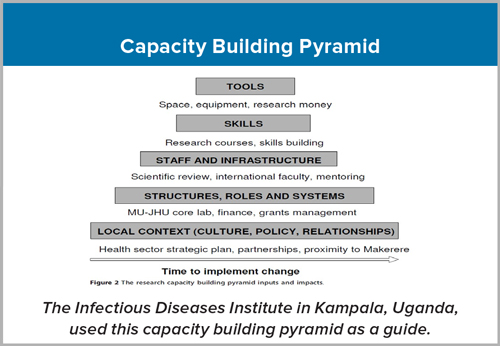

“The research capacity building pyramid became the focus and the guide of everything that occurred at the institute when I worked there,” says Manabe. At the top are the easy things to accomplish, such as bringing in tools, equipment, and research money. The next step on the pyramid is skills. “So equip the person, right? We all know how to do that with courses and training,” says Manabe. Harder tasks to complete—such as developing a core staff, infrastructure and systems—requires the help of international faculty to fill specific gaps and to provide mentorship. The final step encompasses the most difficult goals, including comprehending and interpreting local context (to appropriately assist the country’s Ministry of Health) and building enduring partnerships.

As it matured, the institute necessarily updated its strategic plan, Manabe notes. The first plan reflects “the era of dependence. It's narrowly focused. You're still trying to build a critical mass of talent and training key staff abroad. Grants are led by external partners.” The second strategic plan reflects a new era, that of independence. “We could replicate most things in-country. We’d partnered with policymakers. We had key staff and a larger group of funders. We started to disseminate knowledge to others on the continent.” With its third strategic plan, the institute entered the era of interdependence. “We've become a national node within continental networks. We have global and regional links and sustainable funding. We get major grants directly. Talent comes to us.”

Today, the Institute is considered a true center of excellence able to foster independent researchers, says Manabe, who spoke to Fogarty fellows attending the Fogarty’s

Launching Future Leaders in Global Health Research Training (LAUNCH) Program orientation in July. “Now people try to steal [talent] from us, which is the surest sign of success.”

Intention, direction

Management is a crucial element when building and strengthening research workforce and infrastructure, Manabe says. A fortunate series of excellent executive directors set in motion the original vision of an infectious disease institute in Kampala, organized the IDI’s portfolio, and built the many systems necessary for participation in multi-country clinical trials. Dr. Andrew Kambugu, the current executive director, has “consolidated the relationship of the institute with Makerere University—which is part of its governance structure—and with the Ministry of Health.”

Strategic planning, considered onerous by many, is also imperative to success, explains Manabe. A set strategy allows an institute to say “no” to things outside its core business so that it can move forward with its own portfolio of research aimed toward public health policy and practice. She adds, “Driven by strategy, we don’t become like Atlas holding up the entire world.”

Reality knocks

Manabe has practical advice for others working in an early-stage enterprise located in a lower-resourced setting. Learn how to do basic equipment repairs yourself, since support may not be easily acquired, she recommends. Use what you’ve got. She enticed experts to visit so that they could provide free help.

In the spirit of chance

favors the prepared mind, she also believes “knowing what your gaps are” is the first step towards solutions. “We always had a running list of the things or equipment we needed, so whenever someone would come, we'd say, ‘Yeah, we would love to participate in this grant, it's part of our core business, but if you could add another aim about this and bring an expert who can train people, then we would be even more excited to work with you.’”

Given the probability that something will always go wrong, Manabe finds it best to “under-promise and over-deliver. Happiness is expectations and reality, so if reality exceeds expectation, the partner/funder is always happier.”

American profits

U.S. research dollars go farther in places where things happen at a much higher frequency, says Manabe. For example, congenital syphilis has risen precipitously over the last decade in the U.S., still it’s more efficient and less expensive to study syphilis in a hot spot where the prevalence is up to 30% compared to 0.01% in the U.S. “Money going overseas actually comes back to benefit people in the U.S. afterwards.”

Add to that, training researchers to answer questions of local and regional relevance increases a country’s human resources, which is important for that nation.

Currently, as director of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Diagnostics for Infectious Diseases, Manabe focuses on point-of-care diagnostics, which enable health care providers to test and treat patients within a single visit, rather than wait for days for test results (with patients needing to make additional visits).

Point of care diagnostics “exploded” during COVID, says Manabe, so she’s trying to get companies to consider the platforms developed during the pandemic for other infectious diseases. (The

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics program was the National Institutes of Health's multi-billion-dollar investment in COVID-19 testing methods.) “For companies, there might be both a commercial and a public health reason to not waste the investment that the American taxpayers have already made—we should be leveraging this investment to improve public health in the U.S. and abroad.”

Cascade effect

So how does Manabe define capacity building today? “Now I think it means a group of friends and colleagues—cultivating your network through training. It also means just getting things done and having a public health impact. You train a few who go on and train 10 and that leads to hundreds of people trained who have an impact on thousands.”

This cascade effect is the joy of capacity building, she says. “In some places, they no longer need us as much as they used to, and that may be difficult egotistically, but maybe the sign of really having made a difference is when you teach yourself out of a job.”

In her own words

HIV was the pandemic of my lifetime. When I was a medical student at Columbia University, it was about a decade after the first recognized case and people were dying of HIV/AIDS in New York City.

The year I started my infectious disease fellowship at Johns Hopkins, 1996, was probably the best year of my life—it was the year we got antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Then in 2006, I went to a meeting in Kampala. The Infectious Disease Institute (IDI) offered me a job as head of research, and part of that job would be to put together observational cohorts and clinical trials to study how to improve the ART rollout in Africa. PEPFAR, which launched in 2003, had begun [ART] rollout, yet unexpectedly people were dying after beginning treatment.

It was really difficult to say no. The number of people who’d died in Uganda was high, almost every scientist I’d met had someone in their family who’d died due to HIV/AIDS. So, I went to Uganda.

Together with a group of Ugandan and North American researchers, Pfizer provided a $35 million grant to establish the IDI in 2002 as part of its corporate social responsibility. They felt it was unconscionable that people in America with HIV could be treated and live a long life, yet people in Africa would not be offered the same opportunity. Richard Brough, who first held a strategy position at the IDI under Alex Coutinho, and later became the 3rd executive director, put the capacity building pyramid at the heart of the short-term, medium-term and long-term investments there. He took a long view from the start and put a lot of money into systems.

For example, IDI put in a tracking system to look at spending and procurement and all of the pieces around a grant. This allowed the place to grow. Later, I put in a data management system, DataFacts, in collaboration with the NIH. We added a regulatory and a monitoring group, and then an electronic system so that if your IRB approval was going to lapse, you’d be notified, and eventually the head of research would be notified. I didn’t want people doing research that had not been IRB approved or where approval had lapsed—that was a reputational risk I was unwilling to take!

By the end of my tenure, I wanted to be able to say,

If you didn't succeed at the IDI, it was not because the context in which you were working was bad. In other words, if you can't do a project at the IDI, you probably should do something else, right? Because it's a place where independent researchers have what they need. It's not perfect, it has issues—fraud is detected every year or two. But with their yearly audits and quarterly risk management, they always find it.

I stayed for five years working both at the IDI and training people on the Makerere University side. After I left in 2012, I continued to do research at both. A couple of Fogarty HIV/AIDS capacity building grants meant I could help train PhD students alongside Makerere’s Dr. Nelson Sewankambo, which is probably why I was given an honorary appointment there. And in 2016, I became a member of IDI’s board of directors.

So, my journey, which looks quite haphazard on paper, has one overarching thread: the HIV epidemic.

More information

Updated August 6, 2025

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.

Related Fogarty Programs