Fetal alcohol exposure research supported by NIAAA in South Africa, Ukraine and Russia improves prevention, outcomes

May / June 2016 | Volume 15, Issue 3

Fifty years ago, alcohol wasn't widely considered a danger to the developing fetus - some doctors even infused pregnant women with high doses of it to prevent premature labor. But, by the 1970s scientists began to recognize the connection between alcohol consumption by mothers and birth defects and developmental problems in their children. Today the consequences are well documented, yet millions of babies born worldwide continue to be affected by the conditions known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD).

In low-resource settings, a complex combination of biological, social and economic factors may contribute to prenatal alcohol exposure. Pregnant women may lack information about risky drinking, have limited access to health care resources and suffer from poor nutrition. In some communities, where alcohol abuse is part of the culture, women may face social pressure to drink or lack other recreational outlets and struggle to stop because of dependency. Another issue is that many women don't change their drinking habits until they realize they are pregnant, often in the second trimester, when damage to the fetus may already have occurred.

Researchers funded by NIH's

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) have been studying concentrations of risky-drinking populations in countries including South Africa, Ukraine and Russia to increase awareness of the issue, prevent or limit the impact of alcohol exposure, and help improve the lives of children who suffer permanent damage from it. NIAAA grantees have advanced techniques to diagnose the disorders. They also have used state-of-the art neuroimaging techniques to elucidate the effects of alcohol on children's brains.

Preventing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

A significant research advance that brought more attention to FASD came in the 1990s when South African geneticist Dr. Denis Viljoen alerted NIAAA to the high incidence of affected children in a wine-producing region, the Western Cape Province. Two decades of NIAAA-supported studies document the area as having the highest prevalence of FASD in the world with as many as 26 percent of children in specific communities affected.

"It was pretty amazing. We had never seen rates that high in a general population," says NIAAA grantee Dr. Philip May of the University of North Carolina. He and his research team have been conducting in-school studies of first graders in communities throughout the region since 1997 to determine the prevalence of FASD and identify the characteristics associated with disorders across the spectrum.

He and other researchers attribute the high rates of FASD in the area to what was a practice of giving farm workers alcohol as part of their payment. Now outlawed, this practice left behind an established pattern of consumption on weekends - including among women, who report drinking as many as eight to 10 drinks a night. "In the communities in which we work, drinking is the major form of socialization and recreation," says May. "There's so much social pressure to be with the group and continue to drink. Trying to quit pulls them out of their normal social network, so it's very hard."

May's research has shown that women at high risk of having a child with FASD can be helped to stop drinking or to drink less while pregnant through motivational interviewing, a type of counseling that encourages positive behavior changes. His team has been studying the use of trained social workers and nurses as case managers who help women set goals to abstain from or reduce drinking during pregnancy; understand the growth and development of the child they are carrying; and identify friends, family and organizations they could turn to for emotional support. The studies found drinking decreased six months into the program, but increased at 12 and 18 months after the baby was born. May says clinics in the area don't have the funding to regularly provide this type of counseling, but the educational pamphlets and videos used in case management in this program are now the standard of care.

May's team also provides liquid nutritional supplement drinks with protein, an array of major vitamins and other nutrients to pregnant women who have low body mass index (BMI) because his prior research has shown a link between low BMI, a number of nutritional deficiencies, and the severity of FASD in children. NIAAA is supporting numerous efforts in several countries to examine nutritional supplements, including the B vitamin choline. A recent study in the Ukraine found that babies up to six months of age, whose mothers took a daily multivitamin, with or without an additional choline supplement, did slightly better on a cognitive development test.

Understanding alcohol's impact on the brain

Neuroimaging is providing important clues on how alcohol consumed during pregnancy affects children's brains. Drs. Sandra and Joseph Jacobson, husband and wife researchers from Wayne State University in Detroit, have also been working in South Africa since the 1990s. The Jacobsons had been using neuropsychological testing to assess the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on intellectual function in a longitudinal cohort of children exposed at moderate-to-heavy levels in Detroit. Using timeline follow-back interviews administered repeatedly during pregnancy, mothers provided detailed information about their drinking on a daily basis. This research has linked prenatal alcohol exposure to low IQ and problems particularly with number processing, learning and memory, working memory, and slower information processing speed.

Using the same techniques to ascertain maternal drinking during pregnancy in Cape Town, the Jacobsons and their collaborator Dr. Christopher Molteno, a developmental pediatrician with the University of Cape Town, conducted the first prospective longitudinal study of fetal alcohol syndrome in which women were recruited during pregnancy and found a very similar neurobehavioral profile in a longitudinal cohort of 170 children, half of whom were exposed at very heavy levels.

Given the unusually high levels of prenatal alcohol exposure in Cape Town and the consistency of the neurobehavioral profile with that seen in the U.S., the Jacobsons concluded that Cape Town would provide an optimal setting to use neuroimaging to advance understanding of the cognitive effects on the children's brains. They have been using a number of neuroimaging techniques including MRI, which measures the brain's structure, functional MRI (fMRI), which documents brain activity while completing a task, and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which assesses brain white matter integrity. Although structural MRI was available in Cape Town, there was no capacity to conduct fMRI or DTI. The Jacobsons initiated a collaboration with Dr. Ernesta Meintjes, a University of Cape Town-based physicist, which was funded by a Fogarty International Research Collaboration Award. This grant enabled Meintjes to travel to Vanderbilt University to learn how to implement an fMRI study in Cape Town and analyze the data.

The collaborators went on to produce 19 papers from that initial Fogarty grant. Meintjes says this Fogarty fMRI grant "kick started" advanced neuroimaging research in South Africa, as well as Meintjes's neuroscience career. Based on her training and on the first studies generated by this grant, Meintjes was awarded a prestigious research chair and Siemens contributed to the purchase of a scanner that helped launch an imaging research center that Meintjes currently directs.

"My research chair is a direct result of me being a functional MRI specialist in the country," Meintjes says. With her position, came funding for students and post-docs that enabled her to expand her research group. "There's been an enormous amount of capacity building in this field that's really led to the growth of MRI research."

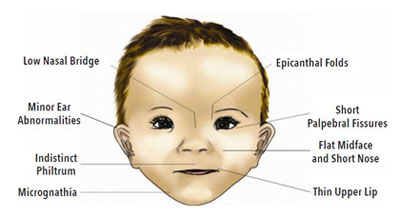

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Courtesy of NIAAA

Description of illustration of child's face showing physical traits associated

with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, including: epicanthal folds, short palpebral

fissures, flat midface and short nose, thin upper lip, micrognathia, indistinct

philtrum, minor ear abnormalities, low nasal bridge.

The diagnosis of FASD can be difficult because not all alcohol-exposed children have the distinctive facial abnormalities and other physical traits associated with the condition and the neurobehavioral deficits are often similar to those seen in other conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Using a method known as eyeblink conditioning - in which people learn to blink to the sound of a tone in anticipation of an air puff administered to the eye - the Jacobsons found that none of the children with the most severe form of FASD met the criterion for this type of learning compared to 75% of the controls.

"This is dramatic and possibly is a good behavioral biomarker for alcohol effects," notes Dr. Sandra Jacobson. Data from neuroimaging studies conducted by Jacobson and colleagues suggest that this deficit may be attributable, in part, to slower processing of information due to deficits in the brain's white matter, which is responsible for transmitting signals across brain regions during a task.

Children with FASD and ADHD both have problems with math, but as had been shown in the Detroit cohort, the type of problems in number processing was distinct for the two disorders. Some of the earliest Cape Town fMRI studies conducted by the Jacobsons, Meintjes, and their collaborators looked at number processing. Alcohol-affected children and normal controls were each given a simple addition problem to solve while in the scanner. Both groups were able to perform the task, but there was a telling difference - children with FASD had to use more extensive brain regions to do so.

"The interpretation is they had to use a lot more neural resources to do what is a very simple and automatic processing problem for normal children," explains Dr. Joseph Jacobson. Moreover, a greater amount of alcohol reported by the mother during pregnancy predicted lower levels of activation in the principal brain region known to mediate number processing in typically developing children.

Improving outcomes of children with FASD

Children with FASD can have a range of physical, cognitive and behavioral problems that include poor memory, diminished communication and reasoning skills, and difficulty in school, especially with math. May's team has shown specialized classroom instruction can significantly improve language and literacy outcomes. For example, some children with FASD have learned to identify first and last sounds of words, become aware of and produced rhymes, blended syllables, and used word picture cards to build sentences. Other researchers have had success using visual imagery to teach math concepts.

The researchers are also investigating other approaches. One avenue is nutrition - May and other scientists are studying whether regular consumption of calorically rich multivitamin drinks can improve the children's cognitive function. Another track is engaging and training parents to coach their children at home.

"With special attention to stimulate them, their brains can repair to some degree," says May. "Usually some problems with impulsivity and working memory persist, but overall their performance and behavior can be improved significantly."

Some progress on policy, but issues remain

In the years after the high prevalence was established by May and his NIAAA-funded team of scientists, the South African government convened global experts and established some policy guidelines for prevention and management of FASD. They also enacted legislation restricting the sale of alcohol, governing its advertising and mandating labels include health messages, such as warnings that drinking during pregnancy can harm unborn babies.

"When you go to the antenatal maternity clinics, there are posters all over: 'If you drink, your baby drinks.' There's a major effort to cut down or stop drinking," says Dr. Sandra Jacobson. "But, when you are dealing with alcoholism and poverty, it's challenging and there aren't enough services to provide support for the women."

More Information

- Related resources from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at NIH:

- Learn more about work by Drs. Sandra and Joseph Jacobson on the Fogarty-supported project

Neuroimaging Studies of FAS Children in South Africa in NIH RePORTER.

- Related publications:

- May PA, et al.

The continuum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in four rural communities in South Africa: Prevalence and characteristics,

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2016, available online 31 December 2015

- de Vries MM et al.

Indicated prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in South Africa: effectiveness of case management,

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2016

- May PA, et al.

Approaching the Prevalence of the Full Spectrum of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in a South African Population-Based Study,

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2013

- Adnams CM, et al.

Language and literacy outcomes from a pilot intervention study for children with FASD in South Africa,

Alcohol, September, 2007

- Jonsson, E, et al. International charter on prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder,

The Lancet, March 2014

- Coles, CD et al.

Dose and Timing of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Maternal Nutritional Supplements: Developmental Effects on 6-Month-Old Infants,

Maternal and Child Health Journal, 2015

- Jacobson, SW, et al.

Impaired eyeblink conditioning in children with fetal alcohol syndrome,Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2008

- Meintjes, EM, et al.

An fMRI study of number processing in children with fetal alcohol syndrome,

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 2010

- Fan, J, et al.

White matter integrity of the cerebellar peduncles as a mediator of effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on eyeblink conditioning,

Human Brain Mapping, 2015

- Related NIH news:

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.