Focus on suicide: Frugal innovation fights India’s high suicide burden

November / December 2018 | Volume 17, Number 6

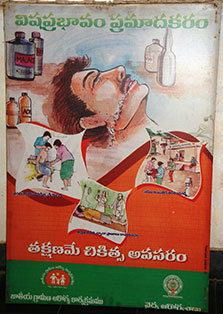

© 2012 Srikrishna Sulgodu Ramachandra,

courtesy of Photoshare

A billboard in India warns of the dangers

of poisoning.

By Karin Zeitvogel

Suicide in India is as complex as it is tragic and preventable. One in three suicides in the world happens in India, where the suicide death rate in women was more than double the global average in 2016 and suicide was the leading cause of death for 15- to 39-year-olds. Stigma and the fact that attempting suicide was a criminal offense in India until 2017 have made it difficult to obtain reliable data about the extent of the problem.

Indian government statistics put the country’s suicide rate at 11 per 100,000, but the WHO estimates the burden is nearly double that.

Improving data-gathering was the necessary first task for Indian researchers after they were awarded a large grant for suicide prevention research and capacity building by the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 2017. An extrapolation of initial data gathered by the scientists at the Indian Law Society’s Center for Mental Health Law and Policy indicates that the annual rate of suicide in India could be up to 40 per 100,000, much higher than the government figures, said Dr. Soumitra Pathare, the lead investigator on the project.

Alongside improving data on suicide, the NIMH-supported project led by Pathare will train implementation researchers, roll out culturally appropriate suicide prevention interventions, and make policy recommendations. In Gujarat state, where nearly three-quarters of the population of 2 million live in rural areas, the researchers are studying ways to restrict access to pesticides, which are involved in around a third of suicides in India. Village officials are being asked to install storage boxes for pesticides in local council offices, where trained on-site managers will “identify people who look distressed when they come to take the pesticide,” explained Pathare. Local farmers would only be able to access the storage lockers during specific hours in the morning and evening, reducing the likelihood of someone “impulsively swallowing pesticide stored in their home after an argument in the middle of the night,” he added. Almost half of suicides in India are unplanned.

A small-scale study, funded by the WHO, was conducted in four villages in southern India in 2013 and found that attempted and completed suicides fell sharply in two villages where pesticide lockboxes were installed. In villages with no storage facility for pesticides, the number of completed suicides went up during the study.

Another intervention on the NIMH-supported project will teach 14- to 16-year-olds to recognize the warning signs of suicide in their peers. In trials in 14 European countries, the Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) program reduced suicide ideation in young people. YAM is being adapted for an Indian context and will be rolled out in schools in Gujarat. Together, YAM and the pesticide locker trials are expected to impact around 200,000 people.

Capacity building is the third prong of the ambitious project. Community health workers are being trained to identify people at high risk for suicide and get those patients on the right care pathway. Pathare and his team will follow up with the health workers to see if the training they were given improved identification and referral rates. Separately, a fellowship is being created to train implementation scientists - essential, says Pathare, to ensuring that evidence-based interventions are scalable.

“This project takes a holistic approach to suicide prevention, looking outside the healthcare system and using ‘frugal innovation’ to reduce India’s high suicide burden,” said Pathare. “The health sector may bear the burden of suicide and suicide attempts, but prevention can happen very cost-effectively in schools and communities, on the internet and through the media. India is a hub for frugal innovation and if what we’re doing in Gujarat works, Indian innovation could be easily translated and applied in American communities, especially rural areas with poor access to mental health care and low-resource inner-cities.”

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.