Vision research leads to new theories on brain plasticity

November / December 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 6

Photo courtesy of Dr. Pawan Sinha/Project Prakash

Photo courtesy of Dr. Pawan Sinha/Project Prakash

By studying how previously blind children in

India learn to see, MIT's Dr. Pawan Sinha has

discovered the brain is more adaptable than

previously thought.

A baby was born blind in a small Indian village. His parents assumed he was just another victim of the family curse, destined to a life without sight like his sister, father and grandmother before him. Blindness is all too common in India, striking one in 100 people.

The parents, resigned to his fate, sent the boy to an institution for the blind when he was four years old. His world changed inexorably a few years later, when health workers visited his school to conduct screening tests and determined his eyes were treatable.

He soon underwent surgery and at last began to see. The scientists monitoring him were astonished to observe his post-surgery vision develop in ways that earlier research had deemed impossible. This discovery not only challenged established views on brain plasticity but may also lead to new approaches for children with deafness or autism.

The boy's screening and surgery were provided at no cost by

Project Prakash, a nonprofit organization established in India to diagnose and treat people with curable blindness. It was founded by Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientist Dr. Pawan Sinha, who was moved to act by a chance encounter with a blind person during a visit to his native India. Begun as a humanitarian program, Project Prakash led Sinha to make surprising discoveries about how the brain develops and humans learn to see. "Prakash," the Sanskrit word for light, signifies both bringing sight to children and illuminating scientists' understanding of brain development.

By treating children and young adults, allowing them to see for the first time in their lives, Sinha has had a unique opportunity to study how the brain learns to process color, shape and movement. "The population of individuals who are blind from birth and who have treatable conditions - these are extremely rare cases in the West," Sinha noted. His patients provide a unique window into the process of visual learning, enabling him to monitor the entire process from day one. Babies are not good research subjects because by the time they can communicate, they've already passed key developmental milestones. Project Prakash patients can verbalize their experience and remain still for brain scans, so scientists can observe how different parts of the brain engage during vision tests.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Pawan Sinha

/ Project Prakash

With research funding from the

NIH's National Eye Institute,

Project Prakash has made

discoveries about brain plasticity

that may lead to new approaches

to deafness and autism.

What Sinha and his colleagues have discovered has turned earlier scientific notions on their head. For many years, researchers believed there was a developmental window for vision that closed at around six years of age. They thought anyone blind from birth would not be able to acquire much visual proficiency if they gained sight later in life. Sinha's patients have forced a reconsideration of those theories.

"Project Prakash is not just benefiting the children who are being treated, but it's likely to have far greater consequences," Sinha said in a recent interview. "That one can directly combine a medical humanitarian intervention with basic science, it's a powerful idea."

Since 2006, the NIH's

National Eye Institute has provided research funding to Project Prakash, which has been "critical" to its success, Sinha noted. Based at the Shroff Charity Eye Hospital in New Delhi, the venture has so far screened more than 20,000 children and surgically treated at least 400 who had curable conditions. Many more have been given non-surgical care such as glasses. Its findings have also led to a petition in India's Supreme Court to ensure every child in the country must be examined by an ophthalmologist before admission to a school for the blind.

Children encountered by Project Prakash have not previously undergone screening or treatment for a variety of reasons, including limited family finances, religious beliefs, distance to hospitals and old theories that sight cannot be recovered after a certain age. "Many parents really don't know whether the blindness that their child has is a treatable condition or not. Some of them believe it is just fate," Sinha said.

Project Prakash research has revealed the brain has significant capacity to "catch up" in interpreting color and light signals to recognize objects, regardless of whether the window was dark during the early stages of development.

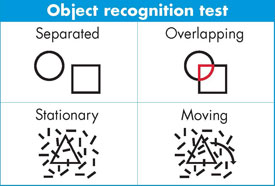

Description of chart of object recognition test:

- Comparing separated and overlapping

shapes - "Separated" shows circle next to square

- "Overlapping" shows circle and square

overlapping, outlines shape in

overlapping area

- Comparing stationary and moving images

- "Stationary" shows triangle overlapping

many scattered dashes - "Moving" shows triangle rotating (arrow

shows motion) among many scattered

dashes

For example, Sinha led one study on object recognition involving three participants, all of whom had gained vision after the age of six. They tried to identify a variety of simple objects displayed on a computer screen. For three months after treatment, they could recognize some objects displayed separately, such as a triangle or a circle, but tended to identify a third object when the shapes overlapped. (See "How We Recognize Objects" diagram at right).

Additional tests showed that motion aids the brain's ability to distinguish individual objects, which was a key finding in the science of blindness. For example, the participants could see a triangle displayed among scattered lines more readily when it constantly moved than when it was stationary. (See "How We Recognize Objects" diagram at right.)

Whether blind people can, on gaining sight, immediately learn to visually recognize objects they previously knew by touch has been a mystery. Sinha and his colleague Dr. Richard Held conducted a series of experiments that showed the brain rapidly - even within a week of surgery to repair the eyes - starts mapping information across the senses about how an object looks and feels.

Project Prakash also uses functional brain imaging pre- and post-operatively to see how children's brains are organized and function in the weeks and months after surgery, Sinha said. Project Prakash studies "are giving us unprecedented and extremely valuable information about how the scaffolding of vision gets set up. They inform our conceptions of basic neuroscience and may be relevant for how we can tackle some neurological problems, conditions that require an understanding of brain mechanisms of plasticity."

Among the other fields of science taking a cue from Project Prakash findings is autism. "Some of the visual impairments that have been reported in the domain of autism are very similar to the kinds of impairments we find in the Prakash children soon after they gain sight," Sinha said. "We are trying to find out whether this is a superficial or coincidental similarity or something deeper."

Sinha has studied 40 children with autism, testing their visual and auditory patterns, and identified deficits in temporal integration. "Even though superficially autism has very little to do with congenital blindness, it can benefit from the same kind of model as Project Prakash, merging the provision of medical care with the opportunity to learn more through research," he added.

Another potential application is with deaf children. "Exactly the same sort of idea would apply to deafness as to blindness: Would the brain of a child who has been deaf from birth be able to acquire auditory processing capabilities, would he be able to acquire spoken language even if he is treated several years after his birth?," Sinha wonders.

As for the children who are currently untreatable because of damaged eye structures, Sinha dreams that one day they will gain eyesight as well. "Having cortical prostheses is way down the road, but at least conceptually, one can imagine feeding information derived from a camera directly to the cortical regions of the brain and enabling vision."

The light shining from Project Prakash is reaching other developing countries with high numbers of blind children - such as Bangladesh, Brazil and China - where officials are studying Project Prakash so they can replicate its success.

For the blind boy who had cataract surgery at age seven, his eyesight now measures 20/100. Within ten months of his operation, he'd learned to see and identify static objects. For him, and a growing number of Project Prakash patients, the light now glows brightly.

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.